Book Reviews

Felecita T. Williams

Felecita T. Williams

Because of Prayer

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2010. $20

ISBN: 0-913441-68-6

Nicolaas, Quito. “Leven met hoop.” Caribe. 10 Sept. 2010.http://caribemagazine.nl/bloggen/literatuur/leven-met-hoop.html

George Lamming

George Lamming

Sovereignty of the Imagination – Conversations III

Language and the Politics of Ethnicity

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2009. 96 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-46-6

Ledgister, F.S.J. “A region for itself.” The Caribbean Review of Books. 23 Sept. 2010.http://caribbeanreviewofbooks.com/

Badejo, Ade Fabian. “Sovereignty of the Imagination – Bearing the honour of many men.”The Daily Herald (Weekender) 6 June 2009: 4+. www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Outar, Lisa. Introduction of George Lamming. George Lamming Reading and Book Signing.Caribbean Studies Association 34th Annual Conference. Jamaica. 4 June 2009.www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Paquet, Sandra. “The burden of authorship, and what it means to bear witness.” Introduction to the book launch. 7th annual St. Martin Book Fair. St. Martin. 6 June 2009.www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Singh, Rickey. “‘Conversations’ of George Lamming.” Trinidad & Tobago Express 2 Aug 2009. www.trinidadexpress.com

Singh, Rickey. “OUR CARIBBEAN: Lamming’s inspiring Conversations.” Nation News 31 July 2009. www.nationnews.com

Singh, Rickey. “Race, Politics, & Culture.” Jamaica Observer 2 Aug 2009.www.jamaicaobserver.com

Singh, Rickey. “Race, Politics, & Culture – ‘Conversations’ of George Lamming.” Guyana Chronicle 2 Aug 2009. http://www.guyanacaribbeanpolitics.com/commentary/rsingh.html

Marion Bethel

Marion Bethel

Guanahani, My Love

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2009. 72 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-96-1

Campbell, Christian. “Born Again – Marion Bethel’s Guanahani, My Love.” Montague 1 May 2010. http://mtmkobbe.blogspot.com/2010/05/guest-feature-by-christian-campbell.html

Campbell, Christian. “Born Again – Marion Bethel’s Guanahani, My Love.” Offshore Editing Services. June 2009.

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

The Salt Reaper – selected poems from the flats (Audio CD)

Music mix by Angelo Rombley

Philipsburg, St. Martin, Mountain Dove Records/HNP

2009. Audio CD, Spoken Word/Poetry $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-94-7

Reyes, Clara. “Is Lasana Sekou writing St. Martin’s story? A fresh look at The Salt Reaper poetry/music CD.” The Daily Herald (Weekender) 23 May 2009: 1+.www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Howard A. Fergus

Howard A. Fergus

I Believe

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2008. 88 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-95-4

“I Believe.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Aug. 2008: 55.http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Rahim, Jennifer. “I Believe – Searching for an indigenous voice and aesthetic.”

Introduction to the Book launch. 6th annual St. Martin Book Fair. St. Martin. 7 June 2008. www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Howard A. Fergus

Howard A. Fergus

Love Labor Liberation in Lasana Sekou

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2007. 184 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-87-9

Badejo, Adekunle Fabian. “Howard A. Fergus’ Love, Labor, Liberation in Lasana Sekou.”The Arts Journal (Vol 5: 1-2) Mar. 2009: 113.

“Love, Labour, Liberation in Lasana Sekou.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Feb. 2008: 57. http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Nowak, Mark. “Labor Love.” Harriet. Poetry Foundation. 2008. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2008/07/labor-love/

Chiqui Vicioso

Chiqui Vicioso

Eva/Sión/Es • Eva/Sion/s • Éva/Sion/s

Spanish, English, and French edition

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2007. 112 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-67-8

Candelier, Rosario Bruno. Del yo al nosotras – El fondo metafísico de eva/sion/es”, de Chiqui Vicioso. DarioLibre.com 28 de Junio 2009.http://www.diariolibre.com/noticias_det.php?id=200198

“Eva/Sión/Es, de Chiqui Vicioso, logra buena acogida internacional.” Diario Libre – Revista 11 de Julio del 2007. http://www.diariolibre.com/app/article.aspx?id=112441

“Eva/Sión/Es de la poeta dominicana Chiqui Vicioso bien recibido desde México hasta Hong Kong.” Caribseek News (2007).http://news.caribseek.com/Sint_Maarten/article_52094.shtml

“Eva/Sión/Es.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Nov. 2007: 44.http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Rodríguez, Jorge Emilio. “Eva/Zion/s in the Paradise of the Unusual.” Cubanow.net 19 Mar. 2008. http://listas.cult.cu/pipermail/cubanowdigital/2008-March.txt

Rodríguez, Emilio Jorge. “Presentation Eva/Sion/s.” Introduction to the Book Launch. 5th annual St. Martin Book Fair. St. Martin. 2 June 2007. www.houseofnehesipublish.com

Vaders, Hans. “Prachtige dichtbundel Chiqui Vicioso – ‘Zand zonder stranden’.” Amigoe(Ñapa) 29 Mar. 2008.

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

Brotherhood of the Spurs

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2007, 1997. 192 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-86-2

Combie, Valerie. “Brotherhood of the Spurs.” The Caribbean Writer 13 (1999): 273-274. http://www.thecaribbeanwriter.org/nofr_REVdetail.php?volsec=13100

Gross, Andy. “Special Book Review: In Our Stories Begin Our Reality.” The St. Maarten Guardian 1 Dec. 1997: 10-11.

Hodge, Charles Borromeo. “Brotherhood of the Spurs – A Synopsis.” St. Martin Newsday20 Mar. 1998: 5+.

Kobbe, Montague. “The Prose of Diction: Lasana Sekou’s Short Stories.” The Daily Herald(Weekender) 29 Nov. 2009. http://mtmkobbe.blogspot.com/2009/11/prose-of-diction-lasana-sekous-short.html

Ward, Rochelle. “Sekou’s nine stories birthing a St. Martin nation – Discoveries and still more questions.” The Bajan Reporter 9 Mar 2010. http://bajanreporter.com/?p=8880

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka

Somebody Blew Up America & Other Poems

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2010, 2007, 2004, 2003. 82 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-79-4

Horton, David Harrison. “Amiri Baraka, Somebody Blew Up America.” Union Herald 25 Sept. 2005. http://unionherald.blogspot.com/2005_09_01_archive.html

Gwiazda, Piotr. “The Aesthetics of Politics/The Politics of Aesthetics: Amiri Baraka’s ‘Somebody Blew Up America’. ”Contemporary Literature, 45:3 (2004 Fall): 460-85.

Johnson, Cedric. “Black radical enigma. and Black Power Politics.” Monthly Review Dec. 2004.

“Somebody Blew Up America, Amiri Baraka.” Rain Taxi Vol. 9 No. 1, Spring 2004 (#33).

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka

The Essence of Reparations

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2007, 2003. 64 pages $15

ISBN: 978-0-913441-92-3

Johnson, Cedric. “Black radical enigma. and Black Power Politics.”Monthly Review Dec. 2004. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1132/is_7_56/ai_n9505450

Drisana Deborah Jack

Drisana Deborah Jack

Skin

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2006. 71 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-78-3

Allen-Agostini, Lisa. “Skin.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Aug. 2007: 33. http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Cooke, Melville. “‘Skin’ saves most feeling for women.” The Sunday Gleaner 16 Nov. 2008: F10.

Rutgers, Wim. “Persoonlijk dichterschap van Drisana Deborah Jack – History seeking remembrance.” Amigoe (Ñapa) 19 Aug. 2006: 11.

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

37 Poems

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2005, 64 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-74-0

Price, Richard and Sally. “Bookshelf 2005/2006 – 37 Poems.” http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/article/viewFile/3589/4350.

Review of Kingdom of the Empty Bellies, by Kei Miller & 37 Poems by Lasana M. Sekou.Journal of West Indian Literature (Spring 2008).

Allen-Agostini, Lisa. “S’maatin poems.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Feb. 2006: 17.http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Cooke, Mel. “A poem per square mile.” Jamaica Gleaner 20 Oct. 2005.

http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20051020/ent/ent1.html

Lansana, Quraysh Ali. “37 Poems.” Black Issues Book Review 1 Mar. 2006: 20.http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1P3-1061610601.html

Shake Keane

Shake Keane

The Angel Horn Shake Keane (1927-1997) – Collected Poems

Philipsburg, T. M Sartin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2005. 184 pages $18

ISBN: 0-913441-66-X

Price, Richard and Sally. “Bookshelf 2005/2006 – The Angel Horn: Collected Poems 1927-1997.” http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/article/viewFile/3589/4350.

Cooke, Mel. “Lifetime of poetry from Shake Keane.” Jamaica Gleaner 18 Nov. 2005.

Morris, Mervyn. “Shake the Poet.” The Caribbean Writer 21 (2007): 230-233.

Nanton, Philip. “All that jazz – On The Angel Horn: Collected Poems, by Shake Keane.”

The Caribbean Review of Books Nov. 2005. www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/nov05/index.php

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

The Salt Reaper – poems from the flats

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2005, 2004. 130 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-73-2

Price, Richard and Sally. “Bookshelf 2005/2006 – The Salt Reaper: Poems from the Flats.” http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/article/viewFile/3589/4350.

Allen-Agostini, Lisa. “S’maatin poems.” The Caribbean Review of Books. Feb. 2006: 17. http://www.meppublishers.com/online/crb/

Arrendell, Francia. “Lasana Sekou pone en circulación The Salt Reaper.” El Nuevo Hispano

8 Nov. 2004: 7.

Beck, Ervin. “Lasana M. Sekou. The Salt Reaper: Poems from the Flats.” World Literature Today Mar. 2006: 58.

Cooke, Mel. “Salt of the earth finds voice.” Jamaica Gleaner 17 Mar. 2006. http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20060317/ent/ent4.html

Cooper, Carolyn. “Pond Salt Rhymes: African Diasporic Knowledge in Lasana Sekou’s The Salt Reaper.” Introduction to the book launch. St. Martin. 6 Nov. 4004.

De Weever, Pedro. “The Salt Reaper … The invitation is on the table.” The Daily Herald(Weekender) 25 Nov. 2006.

Hanna, Mary. “Sekou writes with ‘erotic power’.” Jamaica Gleaner 5 Nov. 2006. http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20061105/arts/arts4.html

“The Salt Reaper: Poems from the flats.” Caribbean Quarterly 1 Dec. 2006. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1P3-1273697561.html

Misani. “Poetry of a divided island.” The New York Amsterdam News 13-19 Apr. 2006: 19. http://www.ruthie-ackerman.com/clips/snapjudgements.pdf

Unigwe, Chika. “The Salt Reaper: Poems from the Flats.” Postcolonial Text, Vol 2, No 3 (2006). http://postcolonial.org/index.php/pct/article/viewFile/470/316

Van Enkevort, Maria, Dr. “‘I’ the female, ‘I’ the white outsider, looking at The Salt Reaper by Lasana M. Sekou.” The Daily Herald (Nov. 2004). http://www.thedailyherald.com/news/daily/h153/book153.html

Fabian Adekunle Badejo

Fabian Adekunle Badejo

Salted Tongues

Modern Literature in St. Martin

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2003. 88 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-62-7

Haviser, Jay, Dr. “Fabian Adekunle Badejo’s book ‘Salted Tongues: Modern

Literature in St. Martin’.” Introduction to the book launch. Second International Conference on Publishing in the Caribbean. Curacao. 29-31 Oct. 2003.

Rutgers, Wim. “Literaire Renaissance in Sint-Maarten – Salted Tongues: Caribbean Culture is One and Indivisible.” Amigoe (Ñapa) (2004?).

Louie Laveist

Louie Laveist

The House That Jack Built and Other Plays

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2003. 97 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-28-7

D’Aguiar, Fred. “The House That Jack Built and Other Plays.” The Caribbean Writer 18 (2004): 295-297

Cynthia Wilson

Cynthia Wilson

Same Sea … Another Wave

A collection of stories

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2001. 72 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-53-8

Gilkes, Michael. “Waving, not Drowning.” St. Martin Business Week 21-27 Jan. 2002: 24.

Scott, Roland B. “Transportation to a Caribbean Past.” The Caribbean Writer 16 (2002): 254-256.

Kamau Brathwaite

Kamau Brathwaite

Words Need Love Too

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2000. 90 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-47-3

Badejo, Adekunle Fabian. “And the Word Was Made Flesh.” St. Martin Business Week (Pt. I) 8-14 Apr. 2002; 20; (Pt. II) 15-21 Apr. 2002: 20.

Bobb, June D. “Giving Life a Tongue: Kamau Brathwaite’s Words Need Love Too.” TheCaribbean Writer 15 (2001): 181-183. http://www.thecaribbeanwriter.org/RevMainFrame.php?volsec=15070

Dawes, Kwame. “Kamau Brathwaite – Words Need Love Too.” World Literature Today 76.1 (2002): 118-119.

Pagnoulle, Christine. “The Reality of Brathwaite’s Words: A Dialogue Between Genres.”Postcolonial Text Vol. 1, No. 1 (2004).

Savory, Elaine. “Journey from Catastrophe to Radiance: a review essay locating Kamau Brathwaite’s Words Need Love Too (2000) in the context of his life and work. Transition Issue 99 (2008): 126-147.

George Lamming

George Lamming

Coming, Coming Home – Conversations II

Western Education and the Caribbean Intellectual

English, French and Spanish editions

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2000, 1995. 112 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-48-1

Holder, Gladstone. “Unchanging Change.” Barbados Advocate 15 Sept. 1995.

McCormick, Jr., Robert H. “George. Coming, Coming Home: Conversations II.” World Literature Today 73.3/4 (2001): 115.

Mohr, Eugene V. “George Lamming. Coming Coming Home: Conversations II.” The Caribbean Writer 10 (1996): 205-207.

Rodríguez, Emilio Jorge. On George Lamming’s Home Return. Cubanow.net 10 Mar. 2008. http://listas.cult.cu/pipermail/cubanowdigital/2008-March.txt

Singh, Rickey. “Our Caribbean: On Lamming and Mills.” Weekend Nation (Barbados) 15 Nov. 1995.

Joseph H. Lake, Jr.

Joseph H. Lake, Jr.

The Republic of St. Martin

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

2000. 90 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-44-9

Wescott-Williams, S.A. “Launching: The Republic of St. Martin by Joseph H. Lake, Jr.” Introduction to the book launch. St. Martin. 3 June 2000.

Drisana Deborah Jack

Drisana Deborah Jack

The Rainy Season

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

1997, 108 pages $15

ISBN: 0-913441-23-6

Gross, Andy. “Guerrilla Poetess Bares Her Soul in Startling ‘Rainy Season’.” The St. Maarten Guardian, 5 June 1997.

Jennie N. Wheatley

Jennie N. Wheatley

Pass It On! A Treasury of Virgin Islands Tales

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers

1996. 91 pages $10

ISBN: 0-913441-26-0

Parris, Trevor. “Jennie N. Wheatley, Pass It On! A Treasury of Virgin Islands Tales.” The Caribbean Writer 12 (1998): 266-267.

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

Quimbé – Poetics of Sound

Philipsburg, St. Martin, House of Nehesi

1991. 136 pages $20

ISBN: 0-913441-14-7

Brice-Finch, Jacqueline, Dr. “Lasana M. Sekou. Quimbe.” Shooting Star Review. 7.i (April 1993): 46-48.

Fergus, Howard, Dr. “Sekou’s work called the cultural ‘Miracle’ of St. Martin.” St. Maarten/St. Martin Newsday 15-21 Nov. 1991: 5-6.

Peters-McKenzie, Joyce. “Quimbé, in which Sekou is a poet of the world.” St. Maarten/St. Martin Newsday 22-28 May 1992: 6+.

Lasana M. Sekou, ed.

Lasana M. Sekou, ed.

The Independence Papers

Readings on a New Political Status for St. Maarten/St. Martin, Volume 1

Philipsburg, St. Maarten, House of Nehesi

1990. 256 pages $20

ISBN: 0-913441-09-0

De Roo, Jos. “Bundel over onafhankelijkheid – Lasana Sekou: ‘St. Martin is ondemocratisch’.” Amigoe (Ñapa) 5 Oct. 1991: 5.

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

Love Songs Make You Cry

Philipsburg, St. Maarten, House of Nehesi

1989. 104 pages $10

ISBN: 0-913441-07-4

Casimir, Nel. “Zevende boek Lasana Sekou: Liefde voor S’maatin.” Amigoe 13 Aug. 1990.

Kobbe, Montague. “The Prose of Diction: Lasana Sekou’s Short Stories.” The Daily Herald(Weekender) 29 Nov. 2009. http://mtmkobbe.blogspot.com/2009/11/prose-of-diction-lasana-sekous-short.html

Peters-McKenzie, Joyce. “Love Songs Make You Cry stirs emotions that lie too deep for tears.” St. Maarten/St. Martin Newsday 15-16 Sept. 1989.

Ten Holt, Asila. “‘Love Songs Make You Cry’, by Lasana Mwanza Sekou. Part 1.” La Prensa

10 Aug. 1990: 10; “Love, Labor, Liberation.” (part 2) La Prensa 17 Aug. 1990: 10.

Ward, Rochelle. “Sekou’s nine stories birthing a St. Martin nation – Discoveries and still more questions.” The Bajan Reporter 9 Mar 2010. http://bajanreporter.com/?p=8880

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

Nativity and Monologues for Today

Philipsburg, St. Maarten, House of Nehesi

1988. 96 pages $20

ISBN: 0-913441-04-X

Fergus, Howard, Dr. “New Caribbean Identity Born.” Caribbean Contact Oct. 1988: 15.

Knowles, Roberta Q. “Lasana M. Sekou, Nativity and Dramatic Monologues for today.” The Caribbean Writer 3 (1998). http://www.thecaribbeanwriter.org/RevMainFrame.php?volsec=3054

Ian Valz

Ian Valz

Masquerade

Philipsburg, St. Martin; House of Nehesi

1988. 70 pages $10

ISBN: 0-913441-06-6

Knowles, Roberta Q. “Ian Valz, Masquerade.” The Caribbean Writer 3 (1988). http://www.thecaribbeanwriter.org/RevMainFrame.php?volsec=3055

Lasana M. Sekou

Lasana M. Sekou

Born Here

Philipsburg, St. Maarten, House of Nehesi

1986. 168 pages $10

ISBN: 0-913441-05-8

Fergus, Howard. “Sekou: A Poet of Protest.” Caribbean Contact Jan. 1987.

Jeffry, Daniella. “‘Born Here’, a turning point in Sekou’s development.” St. Maarten/St. Martin Newsday. 29 Aug. 1986.

Pereira, Joseph (J.P.). “A maturing voice from St. Maarten.” The Sunday Gleaner 30 Nov. 1986: 3C.

Smith, WyCliffe. “Born here.” Amigoe (Ñapa) 13 Sept. 1986.

The following review has also appeared in Calabash – A Journal of Caribbean Arts and Letters, 1.2 (2001): 65-71. www.nyu.edu/projects/calabash

Modern Literature in English in the Dutch Windward Islands: A Brief Introduction1Fabian Adekunle Badejo

Background

The very definition of the geographical location of the three Caribbean islands that comprise the so-called Dutch Windward Islands indicates that things are not what they may seem to be. This is true also for the literature that is produced on the three territories — Saba, St. Eustatius and St. Martin.2 The three tiny islands actually lie leeward and should consequently have been known as the Dutch Leeward Islands. However, with the Dutch West India Company headquartered in Curaçao, the view from down there was obviously different. Similarly, the fact that they are Dutch colonies would logically lead to the assumption that the literature produced there would be in Dutch. As a matter of fact, literature in Dutch on the three islands is virtually non-existent, although among new arrivals from Curaçao and Holland in particular, have been some writers dedicated especially to producing children’s books. Nevertheless, it can safely be stated that there is no current writer of any repute writing in the Dutch language on any of the three islands. The language issue, as we shall later see, plays a central role in the creative output of those engaged in any form of literary production on the islands.

In historical terms, literature in the Dutch Windward Islands has roots in the oral tradition of the territories in a manner similar to what obtains in the wider Caribbean. However, Wycliffe Smith (1981) notes that “very little has been done to preserve the oral literature of the Windward Islands.” Twenty years later, nothing has changed substantially with regards to that observation. He similarly warned that “impinging cultural forces from abroad are slowly eroding the cultural heritage” of these territories.

The “cultural forces from abroad” to which Smith alludes include the pervasive influence of American pop culture via music (radio and lately MTV and BET on cable television) as well as movies and Cable TV sitcoms and soap operas. But according to Smith, those forces also come from the rest of the Caribbean. “Over the years,” he notes, “the folk literature of the (Dutch) Windward Islands has become more and more imbued by West Indian and American influences. The calypso, reggae music, and of late the Rastafarian movement have transformed the lifestyles of particularly the youth. The American way of life, brought about by tourism and the mass media, is very evident in fashion, music and consumer goods on the islands.”

Without diminishing the impact of these influences, Smith’s view however presupposes that the islands had once been immune to such outside influences. This is, however, historically inaccurate. From their very birth, the three islands have indeed attracted foreigners from all parts of the globe. As I have noted elsewhere with regards to St. Martin, the “open-shore, open arms acceptance of foreigners forms a fundamental aspect of the character of the island. Being an island of immigrants who, in turn have known the sweet and seamy sides of emigration, tolerance of foreigners has become connatural to the inhabitants.”3 Foreign influences have therefore not been inimical to the development of an authentic culture in the Dutch Windward Islands, nor have they stultified the growth of this, as Smith seems to suggest, but rather have been (and continue to be) the very strands from which an autochthonous culture has been woven (and continues to be woven).

The difficulty in finding a body of literature that can be easily identified as being peculiar to St. Martin and the other two Dutch Windward Islands is, in part, due to the erroneous approach of trying to sift out those “cultural forces from abroad.” In other words, all attempts to define St. Martin culture as something essentially separate and distinct from Caribbean culture is doomed to remain an exercise in futility. It is, however, curious to note that, despite centuries of Dutch and French domination, European influence continues to be minimal in comparison to the American and Caribbean influences Smith observed.

With regards to literature, it is also noteworthy that a tradition of literary criticism has not fully developed on the islands, with Smith being a lone pioneer in this area, although strictly speaking he can be better classified as a literary historian. The development of literature has been inhibited by this, although there are several capable critics on the island such as Daniella Jeffry, Napolina Gumbs, Rhoda Arrindell, Alex Richards, Alain Richardson, etc. whose incisive critical comments have served as introductions to several of the publications of House of Nehesi Publishers.

The Language Issue

But a more important constraint has been the language question, linked inexorably to the colonial educational policies pursued on the islands. Although it can be said that virtually all the languages spoken in the Caribbean can be heard on St. Martin, St. Martiners themselves are not really polyglots, even though they are often multi-lingual. They normally speak English at home, study in Dutch (or French) at school, and often socialize in Spanish and/or Papiamento, which many of them have learned as a result of having been born in Aruba or Curaçao, or having had to pursue further studies on those Papiamento-speaking islands. Their command of these languages is, however, quite often suspect, while the fact that their mother-tongue is not the official language of instruction at school often undermines their self-confidence in expressing themselves especially in written English.4 As a result, they do not really speak nor write any of these languages confidently enough nor at a very high level of proficiency to enable them to express themselves creatively. It is no wonder then that those who have produced any tangible and noteworthy body of literary work mainly studied in the United States of America. These include “veteran” writers like Smith himself, who has written two volumes of poetry, the late Charles Borromeo Hodge and younger writers such as Lasana M. Sekou and Drisana Deborah Jack.

There is another group of writers who, notwithstanding the educational system imposed on them, have added their voices to the literature of the Dutch Windward Islands. These include the short story teller and artist, Ruby Bute, who has published two volumes of poetry; actor-drummer and poet Ras Changa; actor-director-playwright Louie Laveist and journalist-poetess Esther Gumbs. The two groups of writers use language quite differently, with the first exhibiting a great measure of self-assurance, while the latter’s works have apparently undergone quite a lot of editing, especially for syntax and grammar. It is consequently understandable that out of the two groups, only Sekou, a trained journalist and former editor of the island’s oldest newspaper, Newsday, and Smith, an educator and former president of the University of St. Martin, have consistently written prose. Sekou has two volumes of short stories and a collection of dramatic monologues to his credit, apart from numerous newspaper and other scholarly essays and articles, while Smith has published the pioneering survey of poetry in the Dutch Windward Islands, Windward Islands Verse (1981).

The language issue is certainly one of the most important reasons why the majority of the published authors write mainly poetry. Many of them shy away from prose obviously because of the language factor. They can quickly claim “poetic license” in their verse, when in fact it could be “licentiousness” — a lack of adequate command of the English language that admittedly results sometimes in a felicitous usage. In addition, the discipline, proficiency, and craft needed to write short stories, plays or full-length novels may be lacking in some authors of poetry.

Recent educational changes have resulted in the use of English in a number of primary and secondary schools as the language of instruction. Though slow in materializing, these changes, coupled with a greater awareness of the role of language in the development of culture, as well as the growth of the print media in the last two decades, have given rise to quite a lot of literary activity on the islands.

Publishing

But what has without doubt contributed to what can be referred to as a “literary renaissance of sorts” particularly in St. Martin, is the establishment of the small publishing outfit, House of Nehesi Publishers, which has published every one of the writers mentioned above, with the exception of Smith.5 For the first time in the history of the island, a professional publishing house, under the leadership of Sekou, has been able to gain the confidence of budding writers. Quickly establishing a reputation for itself as a serious publisher of quality books, House of Nehesi has become the major catalyst in the development of literature on the islands.

Although plays of Caribbean masters such as Derek Walcott (who has family links to St. Martin) and Trevor Rhone, have had lasting influence on the local playwrights and theater-goers, only a couple of playwrights have had their works published.6 For example, plays by Smith, Linda Richardson, and Louie Laveist, all of St. Martin, and Miriam Schmidt in St. Eustatius, have not yet been published, although some of them have been performed with great success on the islands and abroad. Only Guyanese-born playwright-actor-director Ian Valz, who has made St. Martin his home, has published an award-winning full-length play, Masquerade(1988).7 This does not mean however that theater is not popular on the island. As a matter of fact, it has enjoyed quite some vibrant periods, especially with the works of Valz, Laveist, Sekou and this writer, as well as the immense contributions of theater groups such as the Cole Bay Theater Company, the Independent Theater Company, Theater International, the United Theater Company, Qualichi Players, et al, some of them now dormant or defunct, but all of which staged plays of both local and foreign writers that were well-received by audiences on the islands and beyond.

Classification

In general, the writers can be grouped in terms of their political commitment and ideological inclinations or in terms of their style. Smith in Winds Above the Hills (the first and to date, only published anthology of Dutch Windward Islands verse) classified the authors thematically: those who wrote about nature, those who wrote “patriotic” or “nationalistic” verse, and those who wrote religious and love poems. In addition, he identified “identity” poetry. However, most of these authors defy being pigeonholed — they tackle all kinds of themes, though they often show a predilection for a particular style. Most of them write in free verse, avoiding rhymes and relying more on rhythm and imagery to convey their messages.

Charles Borromeo Hodge

Hodge is perhaps the most notable exception to this general tendency, often employing classic rhyme patterns in his poetry. He can also be considered the island’s nature poet par excellence. In “Green Hills of St. Martin” he extols the natural beauty of the hills, but laments that they are being defaced by excessive quarrying. For him, apparently only Divine intervention would be able to put an end to such “desecration.”

The green hills of St. Martin rise

In regal splendor to the skies,

Veiled by the mists of dawning day

As light and shadow dance and play

Across the eternal slopes serene

And golden valleys in between

Oblivious to the noisy flow

And struggle of man’s world below

Oh Lord by whose supreme decree

These hills once reared untouched and free

We pray that Thou may grant some sense

To those who wreak this vile offense,

And stay the all-destroying hand

That desecrates this noble land,

So that her riches may adorn

Her generations yet unborn.8

Hodge’s rhymes become less labored, less stilted, as he turns his talents to singing the praises of several island beauties in his love songs. Sylvina Gumbs is the “fairest rose that ever blossomed/From nature’s loving toil.” Gracita (Arrindell’s) smile and eyes are all he can recollect from the hard-fought 1994 constitutional referendum campaign.

I’ve tried but cannot recollect

Which option won the prize,

Yet every moment brings to mind

Gracita’s dancing eyes.9

And of the youthful Leslie Bharath, he sings:

If classic beauty, youth, and grace,

Are but a woman’s curse,

Then Leslie bears a burden which

By far outweighs the worse.10

But beauty, charm and grace can rip open the jealous vein of the poet as when he writes about a lost love in “Heartbreak”:

Somewhere beneath a star-swept tropic sky

Some brute’s vile heart against her own is pressed,

And his rude ears rejoice to hear her sigh

With passion burning in her panting breast;

Somewhere my princess dreams beneath her palms

Lulled by the music of the wind and sea,

While I afar bemoan her elf-like charms

And wonder if she sometimes thinks of me.11

And he shows his often-concealed humorous side when he states what many Caribbean men consider the canon of female beauty in “Those Big Bouncing Beauties” when he sings:

What others see in skinny girls

I’ll never comprehend

I’ll trade the whole bunch any day

For one plump lady friend.12

The “Sekou school”

The modern era of literature in the Dutch Windward Islands starts with Sekou. His return to his native St. Martin in the mid-1980s, after receiving his Masters degree in mass communications from Howard University — and before that studying under Amiri Baraka at the State University of New York at Stony Brook — marked a turning point in the development of modern literature on St. Martin and the other two Dutch Windward Islands. The quality of his literary output, in verse, prose and drama, has earned him regional and international recognition as one of the leading and most exciting poetic voices in the Caribbean, while his excellent pioneering work at the House of Nehesi Publishers, seeking out and publishing new literary talent, place him at the very apex of a new generation of writers who look up to him as an inspiration.

With regards to his publishing activity, I stated in my keynote address at the official simultaneous launching of Kamau Brathwaite’s latest volume of poetry Words Need Love Too and of the Spanish translation of George Lamming’s Coming, Coming Home: Conversations II 13 at CARIFESTA VII in St. Kitts that the St. Martin experience shows that “before the establishment of House of Nehesi Publishers, very few St. Martin writers had been published and the one or two of them who ventured into self-publishing had to peddle their works among friends and family, and even had to give away their books. Today, there are about a dozen writers, whose works were published for the first time by House of Nehesi, and their works can be found in bookstores, the larger supermarkets, gift stores and even in the hands of newspaper vendors! Some of their publications have been sold out and reprinted, and at least three are being used as text books in universities in the USA and Canada. Book parties such as this one to launch new titles have become an important part of the cultural calendar of the island, and continue to attract hundreds of people, who come ready to purchase the books.”14

What Sekou the prolific poet may have given up in terms of the quantity of his literary productions, due to his work as a publisher, he has no doubt gained in the maturity and quality of his work as well as in the inspiration he offers to others. In fact, a Sekou-school is discernible with disciples such as Drisana Deborah Jack and Esther Gumbs who have both imbued their quiet political radicalism with a poignant and determined poetic rebellion.

Drisana Deborah Jack

Jack describes her own rebellious spirit thus:

an errant thread

a flower gone dead

a squeaky-hinged door

a bend in the way

a rainy sun day

a lazy eye

a sea gone dry

a weathered cheek

a child that won’t speak.15

Jack’s first and only book to date, The Rainy Season (1997), also contains some very brief short stories, including the one that gave the book its title, that should actually be read as prose-poems. With an uncanny talent for subtle irony, Jack writes of the numbing effects of colonialism and materialism that have seemingly conspired to abort the dream of political freedom from the womb of the St. Martin nation:

so we stayed together

my tribe and i

living without a dream

settling for comfortable reality

even if

the comfort wasn’t ours

because we believed the lie

that

free thought would enslave us

and

the grave would be our summit16

But she would throw a defiant challenge later:

i dare you to dream

dare you to dream of songs

sung and unsung

ancient and unborn

songs of rebellion

songs of freedom

of love and loss

of protest and peace17

Calling Jack’s tone that of “an activist, a fighter,” Alain Richardson writes in the introduction to the volume that she is the “classic angry youth, rebellious yet profound and with a cause,” and Lorna Goodison welcomes her “strong new voice which has come to join the chorus of inspired chanting of Caribbean women poets.”18

Esther Gumbs

Esther Gumbs, another young rebel with a cause, is actually the youngest of the published poets and among the most talented new voices that are fearlessly intoning “redemption and liberation songs” à la Sekou. She uses her verse to cry for the liberation of her island from the throes of colonialism, to speak of her thirst for change, change, which according to her, “will make us hunger for a fight/fight to overcome/alles dat staat verkeerd.” Lamenting the erosion of traditional values, she writes with a tone of disappointment:

we don’t love anymore

my people

my children

we don’t seek neighborhood gatherings

like we used to

we don’t comb the soil of each other’s hair roots

while soaking our flesh with melee and melee

like we used to.19

According to Alex Richards, “her poetry emerges delicate and apparently peaceful; but a centrifugal rage within churns below the surface and the verses come up from the challenge of the depths, escorted by jugglers and masquerades and furiously true to the context that inspired them. She most definitely is inspired by the writings of Lasana M. Sekou, but adds to this virulence, a feminine touch.”20

Ruby Bute

With two collections of poetry — Golden Voices of S’maatin (1989) and Floral Bouquets to the Daughters of Eve(1995), Bute has established a reputation for herself as a fine, mellow poetic voice devoid of any revolutionary ambitions. The first woman to publish a volume of poetry in St. Martin, Bute had already become renowned for her paintings. Poetry for her is not just another creative endeavor, but an extension of the palette and the canvas. Her thematic focus is on women issues — particularly the proverbial strength of the Afro-Caribbean woman — the preservation of traditional ways of life, and the natural beauty of her “Sweet S’maatin Land.” Bute is also a raconteur of folk tales and an art teacher who has been nurturing the talents of a new generation of St. Martin artists some of whom are showing quite some promise. Her profound love for her island, its people and culture finds resonance in her poems as well as in her paintings.

She was chosen as the “overall favorite artist” of St. Martin in a survey commissioned by the House of Nehesi Publishers in 1999, due in part to the best-seller status of her first volume of poetry, Golden Voices. Bute, referred to as “the first dame of St. Martin’s cultural arts”21 is at peace with herself as a woman, as an artist, as a chronicler of a way of life that is being devoured by crass materialism and fierce competition. She writes in the opening poem of her second volume of poems, Floral Bouquets:

I am very pleased

With all the cards

Life has dealt me

Never have I felt so at ease with myself,

Like the smell of sweet outdoor cooking,

Watching flames dance among the coals22

Writing about Bute’s central theme of women in the foreword to Floral Bouquets, Daniella Jeffry23 states that she “celebrates life in its most trying forms” and adds: “The autobiographical flavor of her analysis adds sincerity and profundity to the reality which she depicts with truth and forcefulness.” That “autobiographical flavor” and a relaxed, even conformist attitude to life, permeates the writings of Bute.

Lasana Sekou

Amiri Baraka would be mightily proud of the poetic talent of one of his most outstanding students — Lasana M. Sekou; and so would George Lamming, who, alluding to Sekou’s Pan-Caribbean (and Pan-African) commitment, said of his second volume of short stories — Brotherhood of the Spurs (1997) — “it is his skillful interplay of (ancestral) memory and imagination which allows Sekou to take us across oceans and diverse cultures, domestic turbulence and territorial rivalries, without any feeling of rupture or discontinuity in the central theme of the narrative, which is the discovery and collective self-realization of a Caribbean people, whether their acquired identification be with St. Martin, Aruba, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, Haiti, St. Thomas, Trinidad, Antigua, Saba, Anguilla. There is room for all in this imaginary family which has made of archipelago probably the first example of a global village.”24

In fact, continuity, commitment, a strong sense of identity, of brotherhood, of family — all these elements are among the strong currents that propel Sekou’s imagination and links him — through memory and imagination — to the Harlem Renaissance and to the well spring of tradition-literary and cultural — that has catapulted him to the forefront of a new breed of Caribbean writers.

Inspired by a Renaissance Muse, Sekou’s writing is imbued with a sense of urgency, and a passionate, serious appeal for love and unity as the pillars upon which a new St. Martin, a new Caribbean nation, should build its progress and prosperity. Sekou is a soldier for peace and unity, for love and compassion, launching his powerful guided verbal missiles against every target of colonialism and divisiveness. He is an unapologetic, unrelenting, and indefatigable freedom fighter, using all resources of his abundant talent to fire up his people, to big up the nation, to water the seeds of independence, and light up the torch of self-pride. He has discovered the taste of freedom in the sweat, blood, and tears that swelled the salt ponds of St. Martin; he has un-earthed the unifying symbols — buried in the heap of ignorance and suppressed by centuries of slavery and colonialism — to place them in the hands of a new generation like liberating flags that no gale can blow away.

Sekou, a James Michener Fellow, is in essence a Renaissance Muse, who has leap-frogged into the 21st century with Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” on his lips and the rich blood of all his ancestors flowing through his veins into his pen.

From Moods for Isis – Picture Poems of Love & Struggle (1978) to Brotherhood of the Spurs, Sekou has created a body of work, which has been attracting increasing critical attention. Some of them like Love Songs Make You Cry (1989), his first collection of short stories, Nativity (1988), and Brotherhood of the Spurs have been used as text in literature and history courses at several universities.

Whether in poetry or prose, Sekou deploys a rich and powerful imagery, in the same way Shaka, the Zulu, or Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian “Opener,” must have deployed their conquering armies, with style and intelligence — victory being their only goal. His voice rises above the mundane, far above the pedantic, and curls up like a smoke signal to all the sleeping warriors of the nation, calling them to arms, telling them that there can be no victory without love and labor. The beautiful Black woman that people the muse’s youthful poems in For the Mighty Gods … An Offering (1982) or Images in The Yard (1983) and the ever-present youth are not only poetic personae, but also real torchbearers of a new dawn.

In continuing the oral tradition, which nurtures his poetics, Sekou’s lyrical poetry, and epic verse as in “Nativity,” are not meant only for the pages of a book, but are alive when read aloud. This long performance poem places him in the orbit of the great Caribbean poet, Kamau Brathwaite, not only in form, but in content as well. Nobody recites his work better then the poet himself. His recitals are dramatic performances, which always has his audiences spellbound. The gift of oratory, of flawless delivery, obviously runs through Sekou’s blood, as his father, the legendary journalist, publisher, and politician José Husurell Lake, Sr. was an acclaimed public speaker. Sekou’s brother, publisher Joseph H. Lake, Jr., is well known for his powerful, pulpit-like public addresses. His maternal grandfather, Thomas E. Duruo, was a leading Garveyite and, said the late patriot Felix Choisy, one of St. Martin’s three great orators of the 20th century.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Sekou’s literary output is his refreshing and daring use of language. He himself has described the polyglot and cosmopolitan nature of St. Martiners as an asset yet to be fully developed. “The whole of St. Martin is a language laboratory,” he said in a 2000 lecture to mark the anniversary of the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Nobody has been able to experiment and come up with fresh linguistic formulas for that laboratory like Sekou. The constant code switching from Standard English to St. Martin English to Spanish (and even Papiamento, Kwéyòl, Dutch, and French) and back has become a trademark of Sekou. And rather than stultify or render his poems or narrative difficult to understand, this recourse enhances his message and boosts his aesthetics. He achieves this because it is not a stylistic embellishment but a respectful exploration of the “St. Martin talk.”

Conclusion

From Wycliffe Smith to Lasana M. Sekou and the emerging “Sekou school,” the modern literature of the Dutch Windward Islands has grown by leaps and bounds, quantitatively and qualitatively, to make it deserving of more serious critical attention. The voices of the authors resonate with unbridled imagination, with battle-thirsty eyes set on reclaiming their land, with an impassioned and blood-bonding integrationist kinship to the rest of the Caribbean. The time has come to listen to their songs with eager ears.

Notes:

1. This brief overview of literature in English in the Dutch Windward Islands is based on an earlier article published in the literary journal Callalloo, 21.3 (1998) under the title, “Introduction to Literature in English in the Dutch Windward Islands” and on the article, “Lasana M. Sekou: The Renaissance Muse,” published in the book St. Martin Massive! A Snapshot of Popular Artists, House of Nehesi Publishers, Special Edition, St. Martin, 2000, pp. 21- 27.

2. The 37-square mile island is in actual fact divided between the Dutch and the French. The Dutch spelling “Sint Maarten” was adopted in 1946, as a way of the colonialists claiming the “Dutchness” of the part of the island that falls directly under Dutch rule. Before then, the whole island was referred to as “Saint Martin” which is also the French spelling of the name purportedly given to the island by Christopher Columbus. Since this coincides with the English spelling of the name, (although the pronunciation is obviously different) and seeing that English is the mother tongue of the predominantly Black island population, this has become the preferred spelling used by the more progressive minds. The official Dutch spelling however remains “St. Maarten.” For the purposes of this paper, however, we shall maintain the English spelling. And though we shall continue to refer to the three island territories as “The Dutch Windward Islands,” this paper focuses mainly on St. Martin, the largest of the three, which has witnessed not only a tourist boom, but a cultural renaissance of sorts, exemplified in a great increase in literary production on the island.

3. Claude: A Portrait of Power, IFE International Publishing House, St. Martin, 1989, p. 4.

4. Drs. Linda Richardson, Lectures in St. Martin, 1981 and 1983.

5. With the exception of the survey, Windward Islands Verse by Smith, his other works, including Mind Adrifthave been self-published. The St. Maarten Council on the Arts published Winds Above the Hills, the first and only anthology of verse in the Dutch Windward Islands, compiled and edited by Smith in 1982.

6. Sekou’s monologue, “Casino Man” which appears in Nativity and Monologues for Today (House of Nehesi, St. Martin, 1988) was adapted for the stage as a one-character play by Fabian Badejo in 1997. The play, starring actress Sylvina Gumbs was performed to rave reviews in St. Martin and Curacao that same year. Badejo has since written and directed a full-length play, “The Bad that Man and Woman Do,” (1999) based on the monologue of the same title by Sekou. Other monologues in the book have also been performed in St. Martin.

7. House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 1988. Louie Laveist’s “House that Jack Built and other plays” is currently being prepared for publication by House of Nehesi.

8. Songs and Images of St. Martin, House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 1988, p. 11.

9. -id- , p. 66

10. -id- , p. 71

11. -id- , p. 58

12 -id- , p. 75

13. Both books also published by House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 2000.

14. Badejo, F. unpublished manuscript, St. Martin, 2000.

15. The Rainy Season, Drisana Jack, House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 1997.

16. -id-, p. 16

17. -id-, p. 61

18. -id-, p. xiii

19. Tales from the Great Salt Pond, House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 1996, p. 35.

20. -id-, p. x

21. St. Martin Massive! A Snapshot of Popular Artists, House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin, 2000.

22. Floral Bouquets to the Daughters of Eve, Columbia Publishers, San Francisco, California, 1996, p. 12.

23. -id-, p. 7

About the Author

Fabian Adekunle Badejo, who studied Caribbean literature in Spain, is an author and former Nigerian diplomat who has made St. Martin his home since 1981. In the early 1980s he was the director of the St. Maarten Council on the Arts, and from 1989 to the late 1990s he was the editor of the daily newspaper The St. Maarten Guardian. In 1989, Badejo’s Claude – A Portrait of Power was published by IFE International Publishing House. He has been deeply involved with the cultural and social life of the island, and has done extensive writing on politics and current affairs, and on the nation’s artists and artistic life. Badejo is one of the primary writers of the profiles in the book St. Martin Massive! A Snapshot on Popular Artists (House of Nehesi Publishers, St. Martin © 2000).

The St. Martin Book as a National Product – A July 1 Story1

ST. PETERS, St. Martin (June 28, 2002) — Once upon a time, the noted scholar/author George Lamming said that one of the shortcomings undermining Caribbean societies’ knowledge of self and environment—and thus militating against the engagement of the best possible participatory creation and construction of progress for all of the region’s people—is linked to the fact that even in the countries and territories where there has been a “lively discourse” with the book for over 100 years, most Caribbean people have “not been thought to leave school with the book as a companion.”

The book that should be a best friend, and not just a good friend, is indeed the national book — that is, the books written by authors of the region exploring the fullest range of the national worlds and the world in general through and with the experiences of and between their nations and the world. A good writer indeed writes about what he knows and here is where the reader and text are likely to have their best meeting and exchange, the most exciting grounation, which may be at once personal, familial, societal, national and universal. This is probably what the esteemed novelist Gabriel García Márquez was debating when he warned us against imperialists, cloaked nowadays as globalists — be they political, militaristic, economic or cultural — whose unmediated imported products make us more solitary and unknown (“worserer” yet, to our selves), while thenational literature that evolves, emerges, materializes out of the national book is bound to make us more solidary, more known. The national “stories” in the book, the creative fictions and the researched, speculative, tested or proven facts, are exactly what is inspirational, elemental, and conveyers of the very engagement and production of material history and critically generative of the “lively discourse” that is essential and indispensable to imagining and actually building independent, democratic, productive and prosperous lives, families and countries; forging fraternal relations, mutual respect, love of humanity, and peaceful coexistence among peoples and countries — or just to liberate subject nations and set them on their way to claim their sovereign future. All of that from a book?

|

|

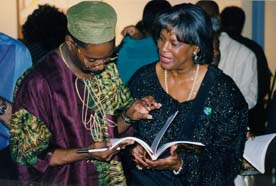

| L-R: Banking officer and humorist Fernando Clark and former commissioner of education Valerie Giterson at a book party discussing St. Martin Massive! A Snapshot of Popular Artists (2000). High school students in South Africa are all smiles after their literary club was presented with copies of St. Martin books in 2001. | |

Okay, here is another way to look at the point being chased in this “story.” A librarian talking about a habit of some St. Martin youths turning in their library card at the Jubilee Library upon graduating from high school, added with astonishment how boldly the young people told her that they won’t need their card any more, “Becausin Oi done with that.” On the other hand, a municipal librarian from Marigot had noted a few years ago that the new French metropolitans, and as far as she knew, the then trickle of Dutch re-settlers from the Netherlands, normally visited the library and set up a relationship for man, woman and child. While the university years and life in general would one way or the other prove to our youths who dis’ the book about the grave error of poor reading habits and of not befriending the book, the librarians’ lament tells of an impoverished relationship with the book that is still too extant — and too close to school, in too many minds, and in too many homes, even if it results in only one child that thinks about being “done with that” reading. The same reading, of the book, of the text, out of which are issued new ideas, new countries, new technologies, new businesses, new solutions, new challenges … in fact the very new cultural products so loved by so many … music, movies, dances, and yes, literatures.

The point of the relationship that is being “wuk’ up” here, as one would trod the road for Carnival, break fertile grounds to plant provisions or raise a new part of an old city, or farm the Freshwater Pond as a fish nursery, or commission a feasibility study to look into opening a new technology trade center within St. Martin’s duty-free regime, or as one would mine the mind to heave forth new and renewing shoots of the people’s genius to generate more sound and creatively original production in culture, education, science, politics and business — has to do with the book in general, the national book in particular and with reading as one of the indispensable combine needed as a life-long companion for personal success and national progress; for advancing the Caribbean civilization that I and I have been laboring and loving for for over four centuries, and for international coexistence. All of that from reading a book?The story of the Flamboyant or “July Tree” has been glorified in the paintings of Roland Richardson, and this year St. Martin’s national tree has been in full, fiery bloom in an uncommon way since May.

|

|

| The story of the Flamboyant or “July Tree” has been glorified in the paintings of Roland Richardson, and this year St. Martin’s national tree has been in full, fiery bloom in an uncommon way since May. |

There is absolutely no indication that book reading in St. Martin is nearing any sort of a revolutionary activity, or even moderately so as should accompany a people, officially in the South and unofficially in the North, in search of a new political/fiscal status or reviving a territory’s stagnant economy — naturally limited as such is in a colony as opposed to the limitless possibilities once engaged progressively in an idependent country. But what is obvious is that the relationship with the book in St. Martin is light years ahead of where it was 20 or as early as 10 years ago. Books that are well researched, soundly written, creatively designed and published in St. Martin may have something to do with the courting of the book, and especially the embracing of the national book as a best friend. Maybe, there, is some seminal evidence of how it is the production of the national book and national literatures that first engender the real friendship for life with reading and the book and the life-inspiring, career-permeating and nation building investment and lasting wealth that is created and generated from that ever-lively companionship.

One of the exciting features of the changing relationship between the nation’s people and the St. Martin book, which is itself a new phenomenon as a “national” product, is a kind of generosity with the book, a sharing of the actual product. It is probably normal with people who read a good book, that they want to talk about it and share copies with others, but given the newness of the weaning St. Martin “book culture” let it be somebody else’s challenge to disprove that this confident inching of generosity with the St. Martin book is more of an expression of the culture of hospitality developed, not during the tourism boom or during that former evil plant, the slave plantation, but certainly so during the Traditional St. Martin period (1848-1963). I first noticed an example of this silent sharing in the late 1980s after about five St. Martin books were published and well-publicized by Newsday, Oral Gibbes, the Guardian, PJD-2, Radio St. Martin and other national media. The poetry, drama, and short stories titles appeared within a span of four years — no way a small feat on the island up to that time, and where until that period, observed literary expert Fabian A. Badejo, there were homes where not a single book was bought and brought into the home as a literary companion by the adults of the home. Here is what appeared as a single sampling of the change that was to come, a known laborer, not known to be a willing reader or purchaser of books, wanted one of these five books autographed. When the author asked him for his full name, he whispered a bit timidly that it was for his daughter. “Tell me how old she is, so I could write something special for her,” said the writer. “She four,” whispered the workingman with calloused hands, then smiling with an almost subversive intent.

The perception or interpretation of the father’s smile as intently subversive might have been wishful thinking or generic memory on the part of the new author. And why not. The brave, beleaguered and beloved ancestors of tens of thousands of people in St. Martin and the millions of people in Nuestro Caribe that are weaning and in want of a creatively known, solidary, lively and lasting relationship with the book were only a historic yesterday ago, just toddling over 150 years, tortured, imprisoned and murdered by their European enslavers for trying to read a word, a sentence, heaven forbid a letter, so imagine trying to open and read a book … like the Christian bible, for example. In St. Martin, there was no exception to this unholy rule and reign of terror against the mass of the African ancestors from 1648 until the emancipation was claimed by the bounded humanity of both parts of the island around July 1848. The people picked the Flamboyant’s blood-flowered branches and waved joyfully to Freedom. Maybe the Flamboyant, also called the July tree by the old ones, was noticed and became part of the national culture by the people’s own consciousness and creative act, because like this year (2002), it was uncommonly lush and in fiery bloom since May. The ancestors, and the more recent older heads, so many whom learned to read and write their own names during the last 80 years, had their earliest relationship with the book in the region, in the Americas, through such a visitation of violence and vile imagery against their manhood, their feminine beauty, their children’s spirit and future; against their Motherland and the space of their new homelands in which they were trying to forge a “society,” invariably in their, our image. To save their very soul and sanity, to save us from the fate of forgetfulness and successfully saving us from being a despicable people without a history, the ancestors wrote, recorded, imagined and read “The becoming of Caribbean people” and the genesis of the national stories in the secrecy of the Ponum, in the syncretic shadows of saints, in the classicism of bachata, camouflaged in capoeria … and so on. This greatest of legacies, the very preservation and generation of our first “known” stories so bequeathed to us in holy vessels of our cultural creations is in fact elemental to the very authenticity of the Caribbean aesthetics that identifies and distinguishes the national literatures as unique and yet as the resilient and ever deepening, expanding, permeating and ascending canon called Caribbean literature.

|

|

| Mrs. Oldine Bryson-Pantophlet (above), principal of the MAVO department of the Milton Peters College has made sure for the last few years that her high school students leave school with the St. Martin book as a companion. This year her graduating class received Lasana M. Sekou’s Brotherhood of the Spurs-a collection of short stories spanning over 300 years of St. Martin’s culture, family relations, travel and imagining of nation. | |

The writing, reading, critiquing, teaching and sharing of the St. Martin book is a natural part of the history, culture and dynamism of this Caribbean literature. The courting of the book as a companion, even its timid and at times toughing use in the island’s classrooms have been evolving thus as part of the region’s story and according to its own “national” creativity and challenges. The sharing feature that may be more celebratory than material history for the scholars, and that has become a visibly exciting characteristic of the changing relationship to the book in St. Martin started to take a more defitive form in mid-1990s, interestingly sharpening in exprssion after Hurricane Luis. Now the St. Martin book has literally become a gift or a prize of value, to pass on with pride to children, to have in the house, to present to a friend, a lover, a parent; to invite the author to the classroom to talk about his or her book. And while the St. Martin book and the national literature, seminal as this combine may be, do not constitute a systemic or curricula staple among the other literatures taught to our children throughout the Dutch and French colonial-based education systems, the profiling of the St. Martin book has reached offices of government by its own and determined merit.

National titles such as An Introduction of Government, National Symbols of St. Martin, Know Your Political History, St. Martin Yesterday, Today, and St. Martin Massive! have become virtual protocol presentations to visiting dignitaries and are sought after as tourism promotion products (in which the native people are not depicted as grinning, unmanly, simple-minded or ahistorically exotic caricatures). It was during the tenure of Dennis Richardson as St. Martin’s Lt. Governor, “functionary” as that office is for the Dutch state’s supervision of its antiquated colonialism, that St. Martiners saw this official, one of their sons, took the courage and confidence in their cultural products, such as the book and present it consistently to visiting dignitaries. Here is a mirrored splinter of the dialogue descended from Legba, Janus, and dem so immortal constructs of humanity in search of causes and causal relationships: Has the practical official use of the St. Martin book been fueling significantly the changing relationship with the book or has the official involvement come about significantly because of the incremental popularization of the national book by the very laborers’ “handling” of the text of the national stories?

Visitors to Sweet St. Martin Land, and folks leaving on vacation are adding to this surely visible and slowly but steadily increasing sharing of the physical product of the national literature. Folks are packing the St. Martin book and taking this new friend along for their own reading and knowledge of the St. Martin people or as a gift to friends and family abroad. The books of Drisana Jack, Borromeo Hodge, Gerard van Veen, Joseph Lake, Jr., just to name a few, have joined the CDs of Beau Beau, Timo, Dow, Explosion and Tanny & The Boys, the Steve Thompson or Baker guavaberry, and the art of Roland Richardson, Joe Dominique, Ruby Bute, Ras Mosera and Cynric Griffith among others, as the authentic folksy or high end creations of the St. Martin culture and of the visitor’s experience in the Charismatically Caribbean island. “We know tourists are buying some of the books made in St. Martin, and for years now teachers and some business people who come to love and respect the St. Martin people carry our books for friends and family during their vacation. But most of our books are bought and read in St. Martin,” points out Jacqueline Sample, president of House of Nehesi Publishers, a non-profit foundation that is still very much dependent on young, adult and senior readers, cultural grant agencies and community-minded businesses that have the courage and confidence to invest in the creativity of the people’s culture—and the wealth and advance to human and national liberation that that national culture generates for the people of St. Martin by their very love and labor.

All of that from a book? All of that and more from books when counted on and counted as our best friends.

1. Sekou, Lasana M. “The St. Martin Book as a National Product – A July 1 Story.” St. Martin Business Week 1-7 July 2002: 8-9, 19.

About the Authors

Marion Bethel is a poet, short story writer, essayist and attorney from The Bahamas. A Cambridge University graduate, Bethel’s writings have appeared in Callaloo, The Massachusetts Review, … Read more

Marion Bethel is a poet, short story writer, essayist and attorney from The Bahamas. A Cambridge University graduate, Bethel’s writings have appeared in Callaloo, The Massachusetts Review, … Read more

Free copy with all HNP orders … While supply last

Free copy with all HNP orders … While supply last

Fete – Celebrating St. Martin Traditional Festive Music

A special culture features publication, song, music, dance, carnival, and more, 48 pp.

Contents: Foreword • Tanny & The Boys • Bèbè recalls • In a fête • Quimbé • Carnival • “Jim Tucker” Samuel • Ray Anthony Thomas Tale of a concert • A blast in The Netherlands • Ponum • A bumper crop • Eat, drink …

Launched at St. Martin Book Fair. A “must read‘ selection by Vogue magazine.

The Adulterous Citizen — poems, stories, essays byTishani Doshi